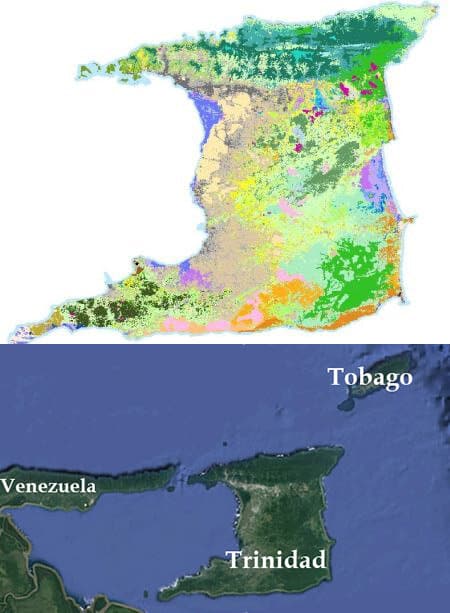

The map of the Trinidad shows the diversity of forest cover. The map at the bottom shows the position of Trinidad, Tobago and Venezuela. Top map from Helmar et al, 2012.

Oliver’s Parrot Snake, Leptophis coeruleodorsus

Oliver’s Parrot Snake,

Leptophis coeruleodorsus

Geographers often consider Trinidad and Tobago the southernmost islands in the Lesser Antilles, but biologists have long known the flora and fauna of both islands are more closely related to those of the South American continent than the Antilles, the islands to the north. Trinidad and Tobago are relatively small islands, but they have a spectacular diversity of amphibians and reptiles – the herpetofauna. This diversity is in part a result of the island’s location between mainland South America and the Lesser Antilles. Additionally both islands have had close contact with the South American mainland multiple times over the past 20 million years. This contact was not only from falling sea levels, but from tectonic movements that eventually positioned the islands in their current locations. The islands have been isolated, connected, and re-isolated from the mainland many times in the prehistoric past. The fauna is decidedly Neotropical and not Antillean. The idea that endemism on Trinidad and Tobago is low – is likely to be incorrect. Careful observation and comparison of island populations and with mainland populations, and comparing molecular data between the island and mainland populations has revealed cryptic species, some endemic, and others that are shared with the Venezuelan Coastal Ranges. Oliver’s Parrot Snake is one of the Trinidad and Tobago species shared with both islands and the Venezuelan Coastal Ranges.

The Trinidad and Tobago climate is tropical with two major seasons: the dry season for the first six months of the year, and the rainy season for the rest of the year. Winds are predominantly from the northeast, dominated by the northeast trade winds. Unlike most of the other Caribbean islands, Trinidad and Tobago lie south of the hurricane belt. In Trinidad’s Northern Range, the climate is significantly different from that of the lowlands. Cloud cover, mist, and almost daily rains in the higher elevations create a cooler, moister climate than the lowland climate.

The flora and fauna of both islands are decidedly South American, with only minor contributions from the Antilles. Despite the shared life forms, the two large islands of the archipelago had quite different geological origins. Part of Tobago originated in the Pacific on the edge of the Caribbean plate, and it traveled to its current position over the past 55 million years. Trinidad, on the other hand, originated as part of the South American continent.

Tobago is about 36 km northeast of Trinidad. The two islands are separated from each other by a channel that reaches a depth in excess of 91 m, but much of the channel is less than 72 m deep. Tobago is 51 km long and 18 km at its widest point. In is approximately 300 km2 in area. The most prominent feature of Tobago (and the area of most herpetological interest) is the Main Ridge. The Main Ridge runs east-west for about 24 km with the highest point reaching 549 m. The surrounding terrain is steep and divided, with ridges and deep gullies cut by fast moving streams. The southwest end of the island is a coral platform and contains remnant patches of mangrove.

Trinidad is divided into five physiographic provinces. The Northern Range is a series of parallel ridges that are an extension of the Coastal Cordillera of Venezuela. The highest peaks are Cerro del Aripo (940 m) and El Tucuche (936 m). The range is cut by a series of northwest–southeast striking faults which abut the El Pilar fault system. The Northern Range is 11–16 km wide and about 88 km long. In profile, it is shorter and steeper on the north side and has extensive foothills on the south versant. Most of the region lies between 150–456 m in elevation, but the majority of peaks and ridge tops are between 456 and 760 m ASL. Fifteen valleys dissect the Northern Range; three more to the west are now drowned and represent open waterways between some of the Boca Islands. Most of the streams are transverse and the largest drain to the south. These southern draining streams have cut deep valleys; the exception is the alluviated Tucker Valley.

The Northern Basin is a dissected alluvial terrace and a peneplain. During the Miocene and Pliocene, as well as during Pleistocene glacial maximums, much of this was covered with water. The basin averages 16 km wide but widens on the western edge to about 25 km for Caroni Swamp (an area of about 103 km2 of mangroves).

The Central Range is a belt of low-lying hills dividing the island into northern and southern halves. The average width is 5–8 km and the elevation varies between 60 and 300 m. The range is diagonal across Trinidad from Manzanilla to Pointe-á-Pierre, a distance of about 60 km. Tamana Hill is the highest point reaching 307 m in elevation. The uplifted Brasso and Tamana formations form the core of the Central Range. The poorly defined Naparima Hill and the Central Range Fault Systems are located on the southern edge. Drainage is mostly to the northwest into Caroni Swamp, and to the southeast into Nariva Swamp and tributaries of the Ortoire River. Shale, quartzite and limestone compose this range.

Southern Basin topography consists of rolling hills below 60 m in elevation. The Naparima Hill Faults divide the basin along a line between Mosquito Creek to Radix Point. To the east the water drains into the Atlantic via the Nariva and Ortoire and to the west the water flows in via the Oropuche River into the Gulf of Paria. Nariva swamp is a 258 km2 complex of palm marsh, mangroves and herbaceous swamp.

The Southern Range is a discontinuous series of low hills, usually below 150 m, that form a barrier to the Atlantic on the southern edge of the island. However, the Trinity Hills in the southeast reach 303 m in elevation. The Erin, Moruga and Piolte rivers all drain southward into the Serpent’s Mouth.

Helmar et al. 2012 shows satellite imagery can provide fine detail of forest types if many dates of imagery are available This is because newly available satellite image archives provide clues to distinguishing among forest patches containing different groups of tree species. Tropical countries need to produce detailed forest maps for a financial mechanism that gives countries incentives for Reducing Carbon Emissions from Deforestation and Degradation (REDD+) and for managing forests to sustain biodiversity and enhance carbon stocks. Detailed maps of forest types, including maps that distinguish groups of tree species, are essential, but until now, scientists have assumed that tropical forest tree communities appear too similar to each other in most satellite imagery to be mapped. The authors searched through the recently opened archives of Landsat satellite imagery and through the very high-resolution satellite images that are viewable using Google Earth from Trinidad and Tobago. They discovered that the spatial distributions of many tree communities, thought to be indistinguishable in satellite imagery, can in fact be revealed, but only in imagery from unique times, such as that collected during periods of severe drought, or when a particular tree species is flowering. Other forest types were distinct in very high-resolution imagery because of unique canopy structure. These maps are the first for an entire tropical country that show the distributions of communities of tropical forest tree species. The study also produced a new set of topographic maps for the country at two scales that depict reserve areas, town, roads, rivers, and other landscape features in addition to forest type. The variety of forests types and the diversity of topography contribute to supporting the highly diverse herpetofauna.

Citation

Helmer, Eileen H.; Ruzycki, Thomas S.; Benner, Jay; Voggesser, Shannon M.; Scobie, Barbara P.; Park, Courtenay; Fanning, David W.; Ramnarine, Seepersad. 2012. Detailed maps of tropical forest types are within reach: forest tree communities for Trinidad and Tobago mapped with multiseason Landsat and multiseason fine-resolution imagery. Forest Ecology and Management. 279:147-166.